Lessons from Real-Time Programming class

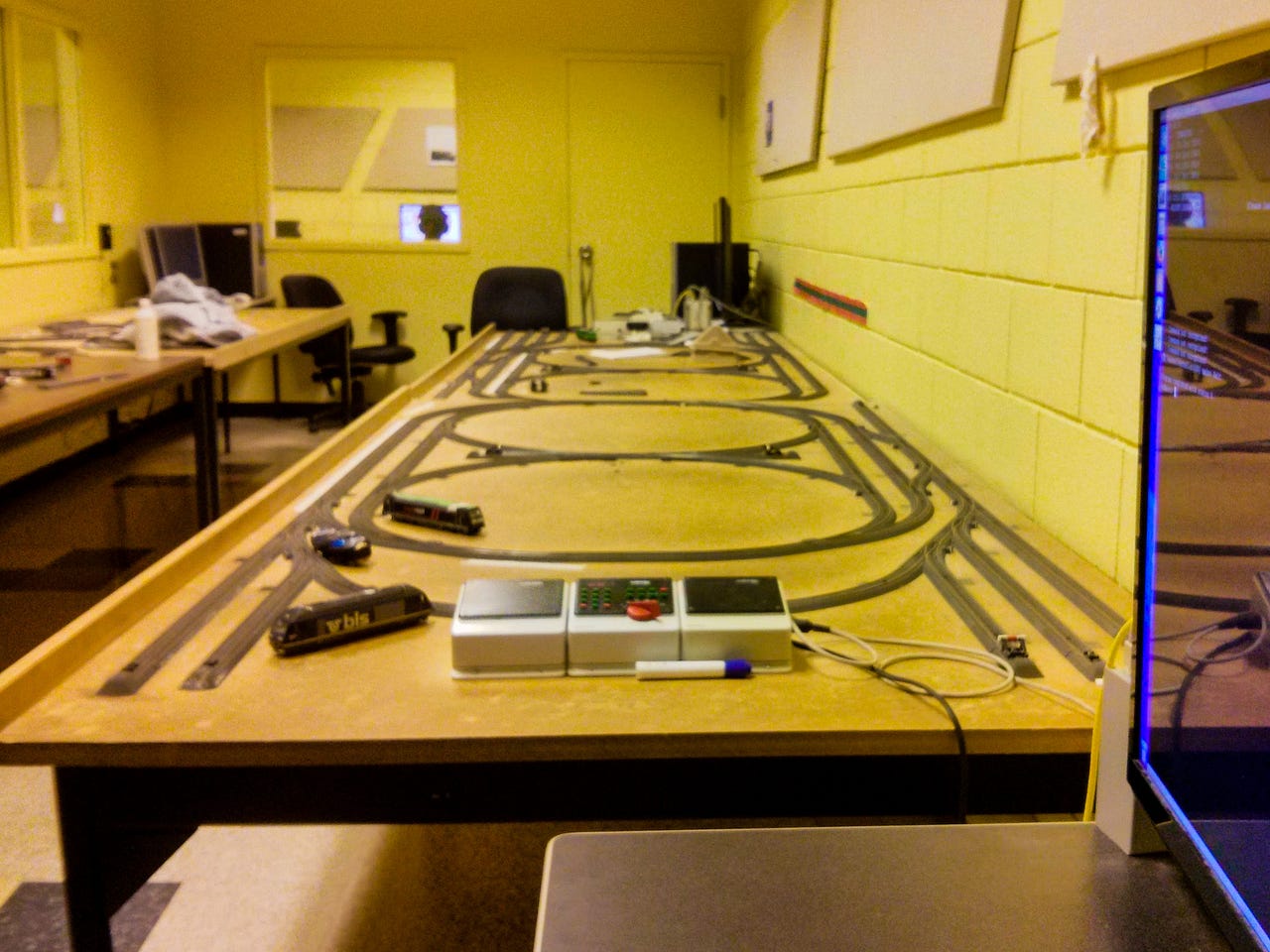

This post is about lessons I learnt in CS452 Real-Time Programming, a 4th year undergraduate class at the University of Waterloo. Better known as “trains” or “realtime” class.

“Easy stuff! You play with trains all day (literally, maybe even night). All you need to do is write one simple program to control multiple trains so they don’t crash!”

— chko on BirdCourses.com

The class is a bit unconventional because it indirectly teaches other topics, like time management and teamwork, by providing a large amount of work — so that you have to learn these skills. I’ll talk about these lessons, hoping to address a more general audience.

History

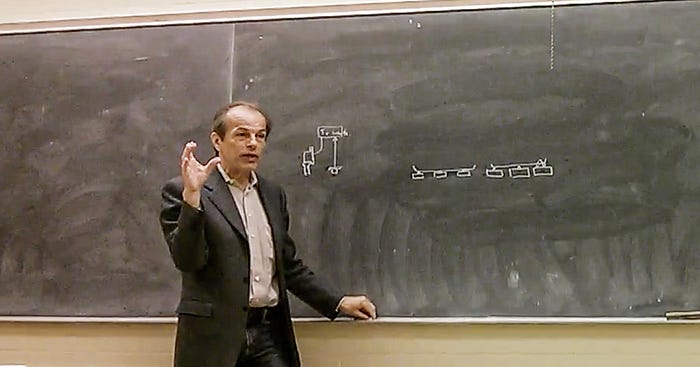

This class has been around since at least the 80’s. Currently Bill Cowanteaches this class, and has been for over 20 years.

The equipment have evolved since then, but the underlying challenges have not.

For example, teamwork, setting priorities, and dealing with real (imperfect) systems.

The early version of the QNX real-time operating system took off from a pair of students taking this class, Gordon Bell and Dan Dodge. They decided to expand the class project into a full-fledged commercial RTOS (real time operating system).

“You should try to find a partner for this class, it’ll be hard without one. Generally I’ve seen two outcomes:

(1) you become friends with your partner, or

(2) you stop being friends and hate each other.

I recommend not starting with a partner who is your friend, because you are already friends. Don’t risk it.”

— Prof. Bill Cowan

Curriculum

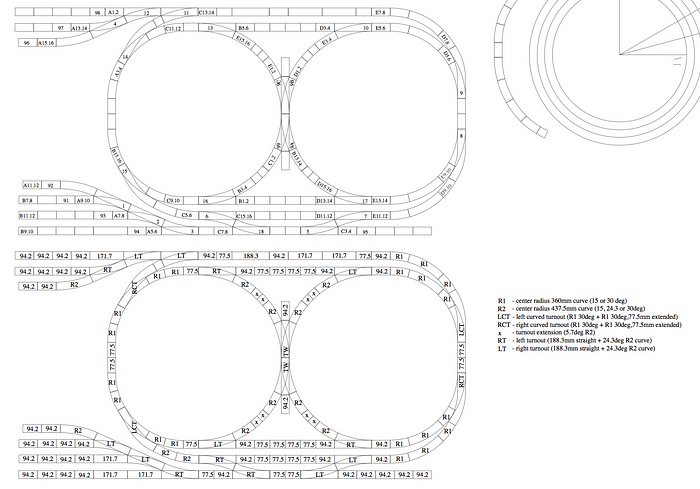

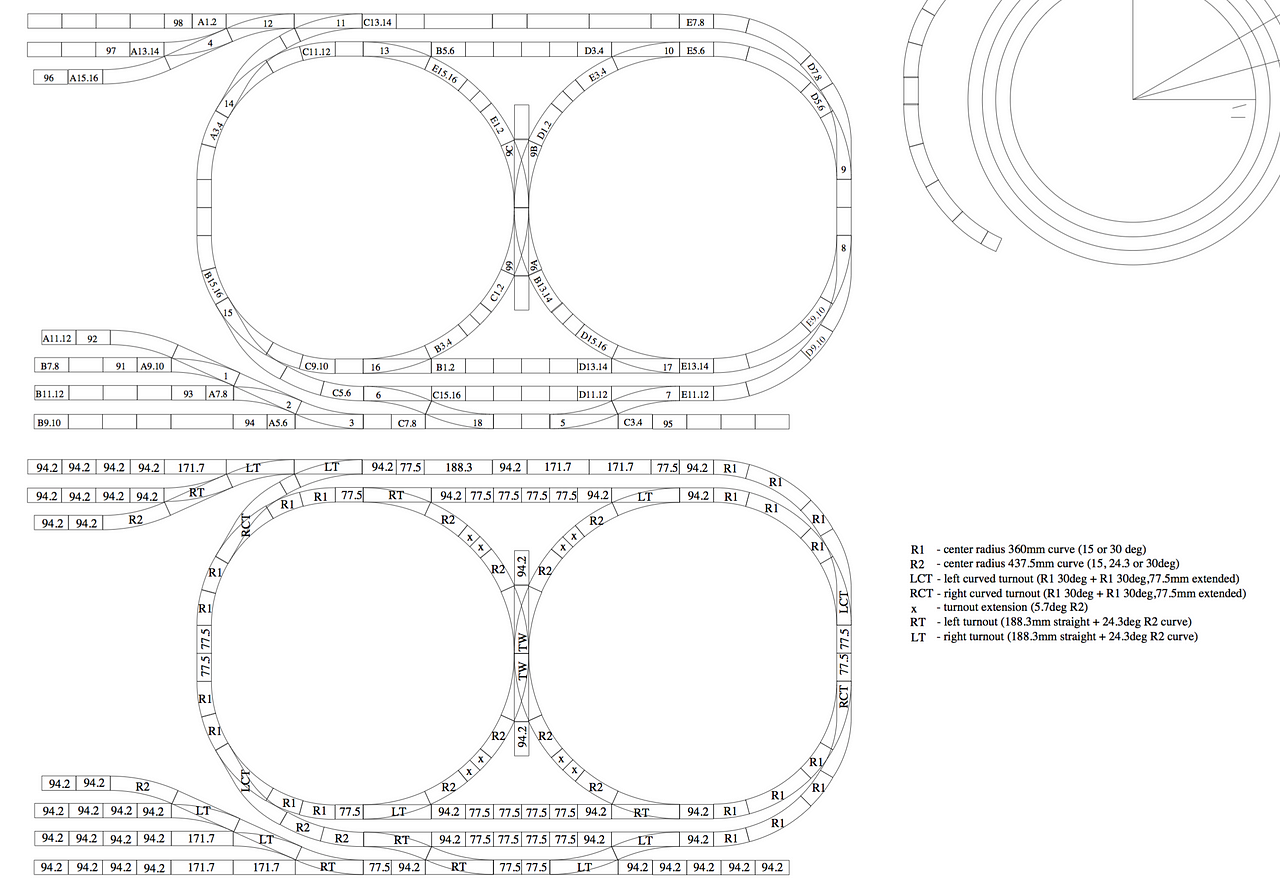

About 65% of the class involves building a small embedded kernel, with the other 35% working on the train management application.

You can choose to program in whatever language you want, because there aren’t any standard libraries provided. People generally program in C, because it’s known as a systems language, and the programming examples given in class. But there’s no reason why you can’t do it in Rust language, for example — although godspeed, you’re venturing into uncharted territory!

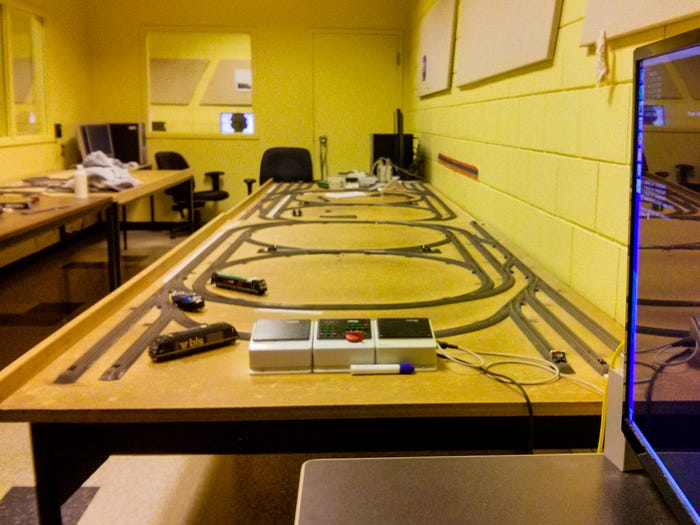

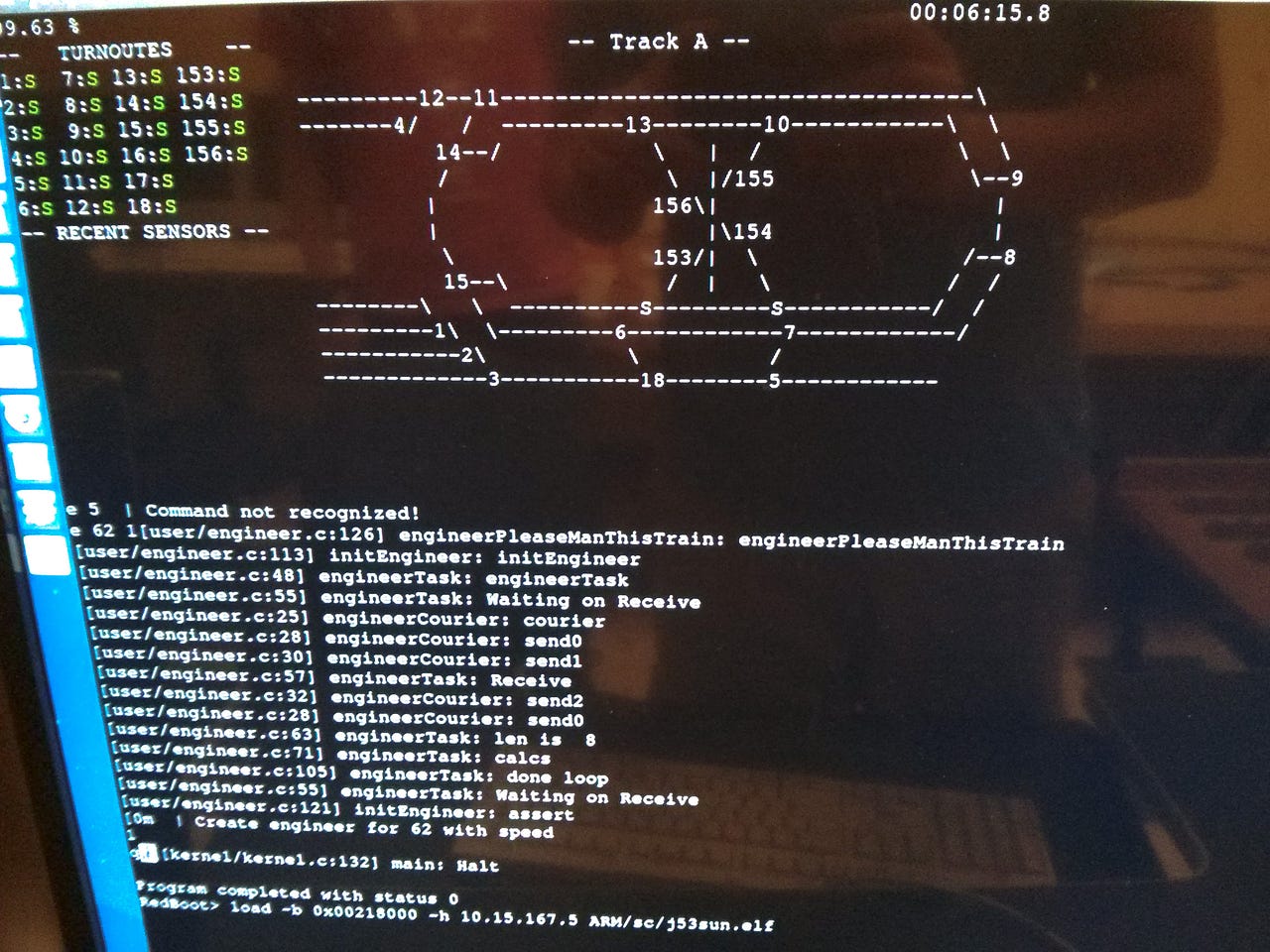

The kernel runs on a TS-7200 embedded system, and it talks to a Märklin Train System over RS232 type serial. The firmware is loaded on via RedBoot, a bootstrap environment for embedded systems.

The final exam is a take home 24 hour long exam, where you can use any resources you want, and you only need to do 3 of the 5 questions. The assignments and kernel make up 70% of the grade.

Optional Technical Info

The microkernel did very little; it

- only kickstarts a couple of initial processes.

- handled message passing between processes.

- provided very basic interrupt handler and clock.

- supports realtime operations; the scheduler is predictable (through priorities, and pre-emption).

- avoided disk IO by loading kernel and programs into RAM directly.

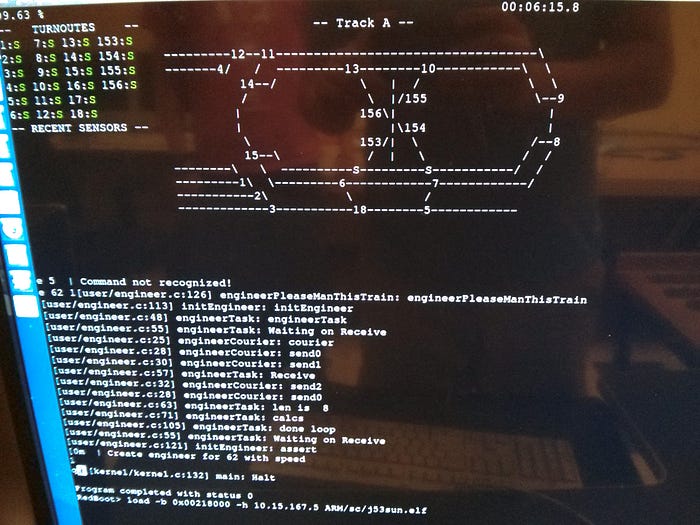

- needed to provide serial output to a PC terminal, to display graphics relating to the real-time actions being controlled, such as displaying position of trains on the track showing movement.

The realtime program is probably more work than the kernel. Because initially there were many constraints, but later on, assignments were of more guidelines than objectives.

Lessons

I’ll talk about some of the lessons I learnt, and provide some reasoning or backstory to them.

Don’t trust anything. Don’t make any assumptions.

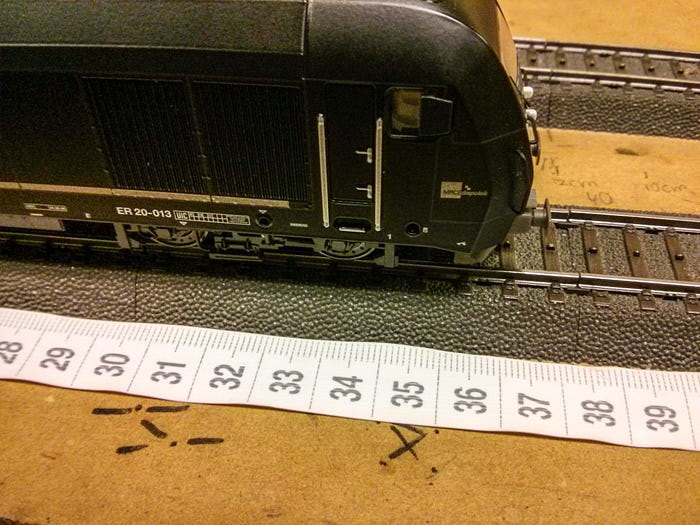

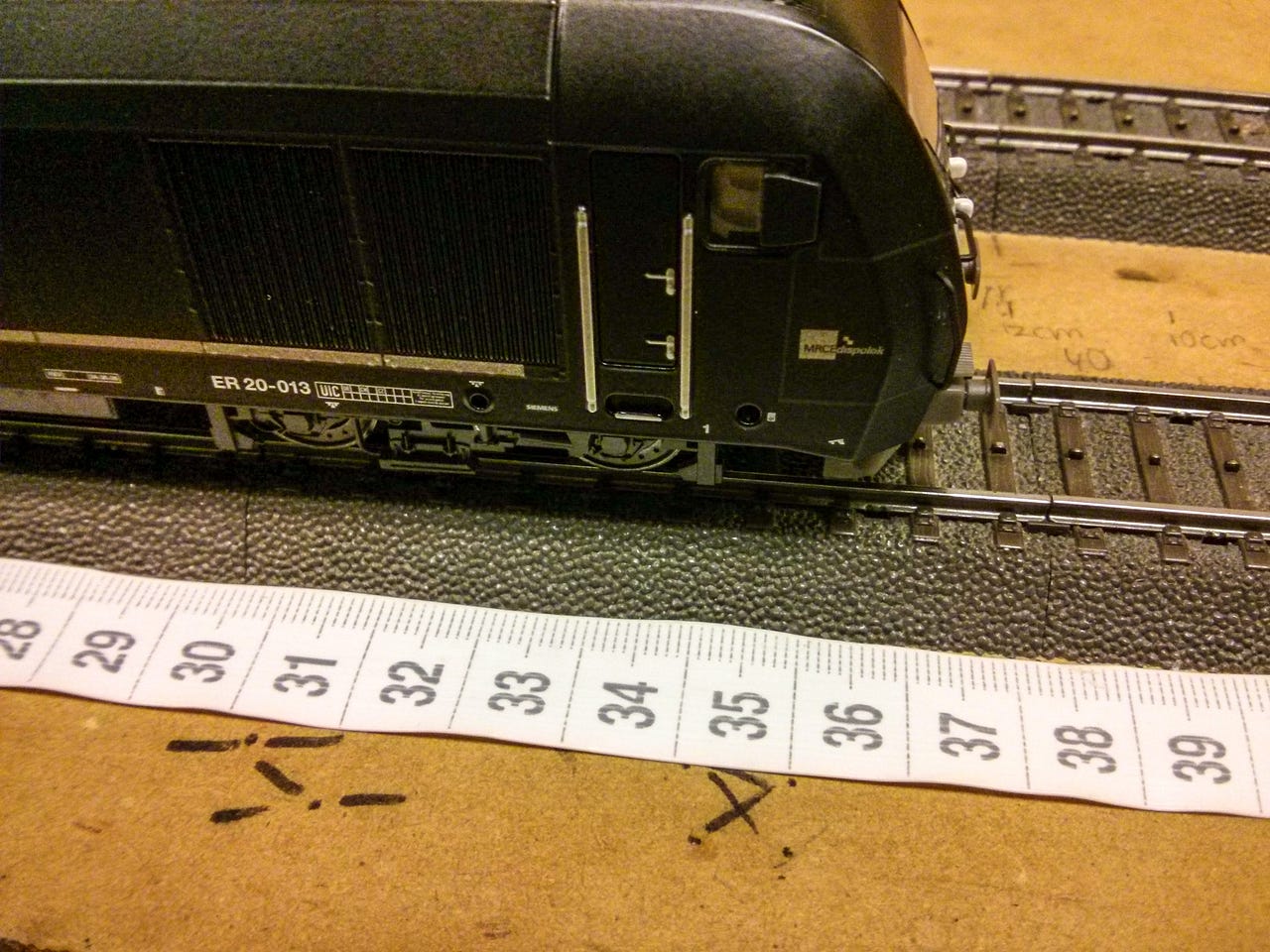

One assumption that was made was while building a acceleration and deceleration profile for the train — that the train would stop where we expected to. Calibration was done by running the train at full speed around the tracks, and when it hits a sensor, tell it to stop.

That assumption turned out false: at max speed, the train varies its stopping distance quite a bit, up to ±3 cm. Not only that, the train accelerates and decelerates non-linearly!

This meant that over the course of several start and stop move commands, there can accumulate quite a difference between where you think the train is, and where it actually is.

Consequently, our model couldn’t be trusted. We’d assume it was safe to perform a certain operation, and it of course, wouldn’t be. And that causes accidents like multi-track drifting to occur.

Multi-track drifting is when you thought it was safe to flip a switch, and then it wasn’t. The poor train comes to a sudden stop because the front axles and rear axles are going to different directions.

When your model of the world and the real world itself are different, you get problems. We couldn’t trust our model. We’d assume it was safe to perform a certain operation, thinking we knew where the train was, and it wasn’t safe.

This explains the comic that is pasted on the walls beside the train set. Now I get it!

If this was a real train, this would result it some serious accidents. A lesson we learnt after trying to figure out how this happened.

Assumptions are going to be wrong! So it’s important to build in error correction and recovery.

Often assumptions are wrong, or become wrong during the course of real life usage. Real systems don’t always run in your ideal situations. You can’t always think of all the edge-cases. Errors are going to happen. Your best chance is to try to realize the error as early as possible and correct for it.

Instead of eagerly switching tracks for the next train, we switched tracks only if the train had ownership of the track.

To solve this, we ended up building in margin of error around where we think the train is, assigned the train to have ownership to tracks, and made sure when trains approach tracks that they didn’t own, it would stop.

You are as only good as your tools.

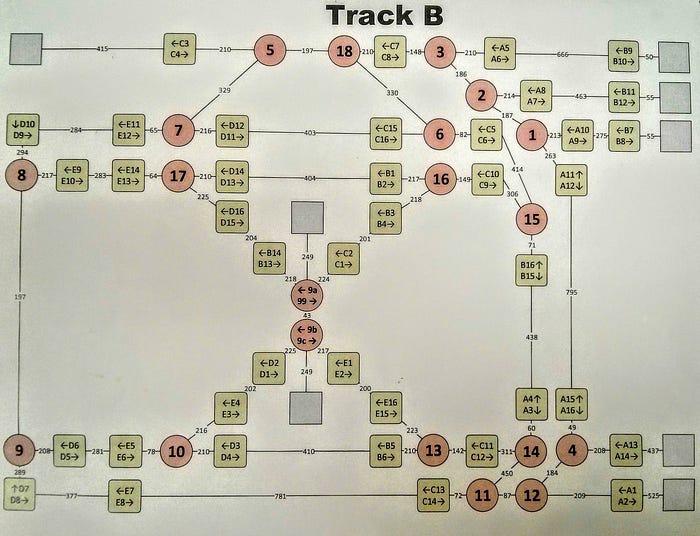

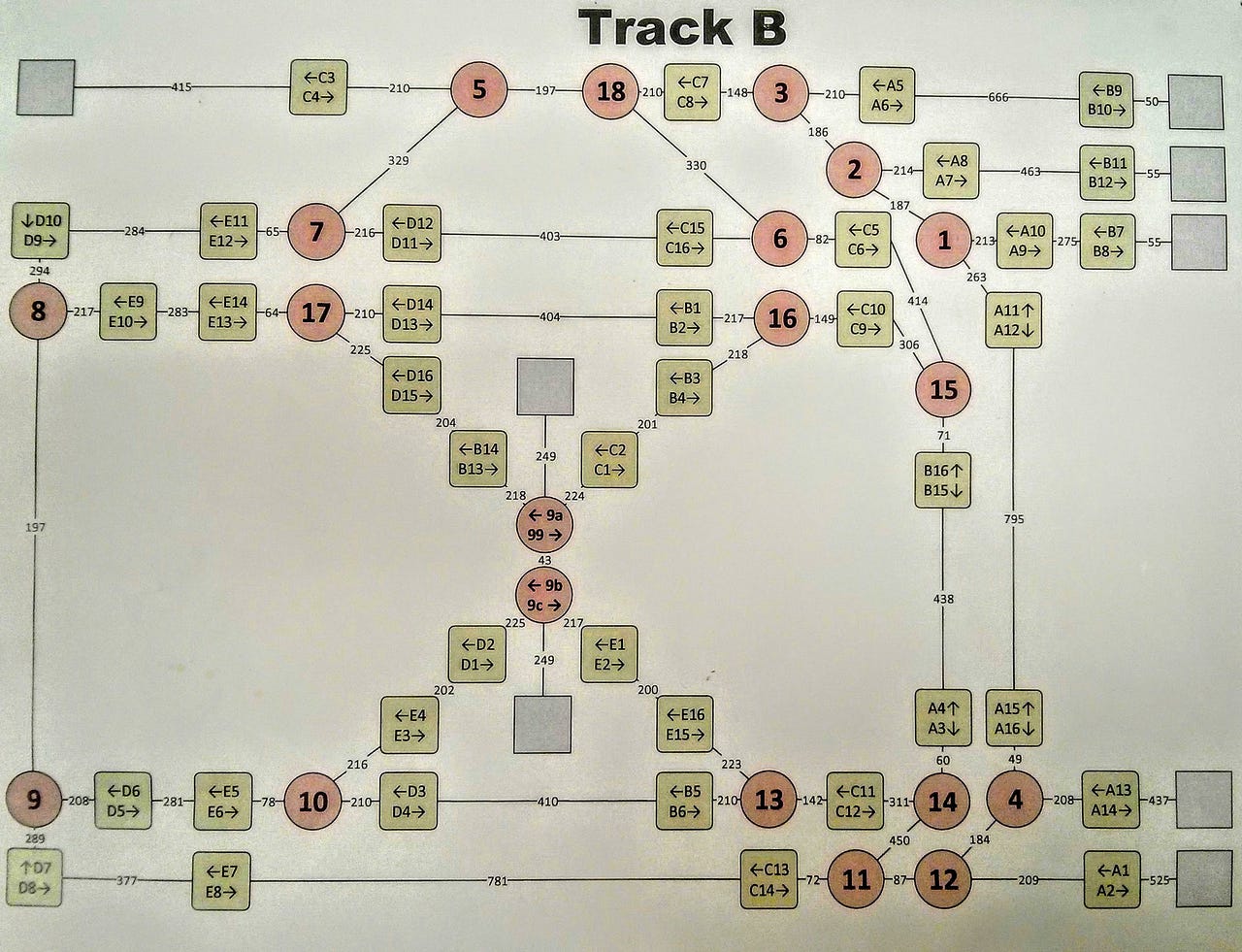

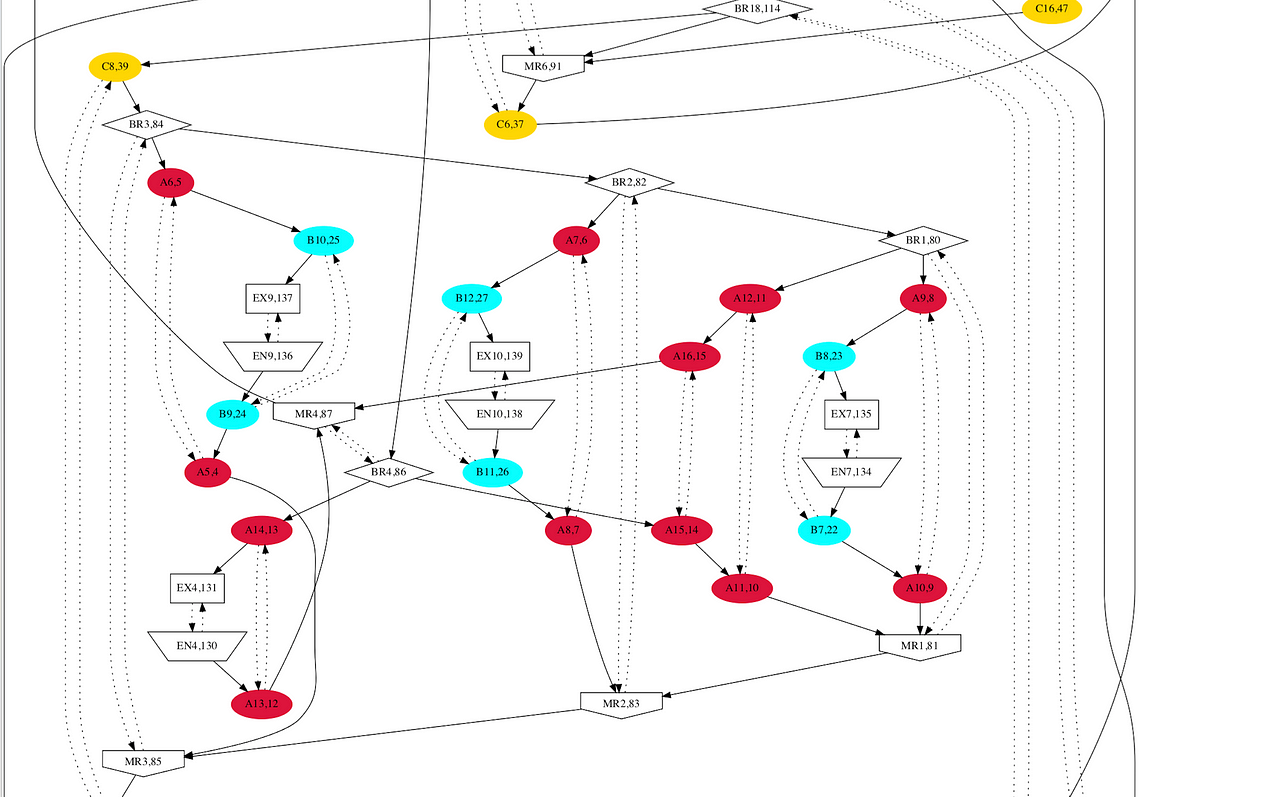

Building the path/route finding portion of the project, we were manually reading a map and trying to reason about what the shortest ways were. This took a long time, and felt complicated.

Route a train from point A to point B was not difficult, but factoring in what paths are currently, or will be, blocked by other trains made it harder. We often stared at the layout map for a long time, trying to figure out whether this was the quickest path through this or not.

After staring at this for a long time, and it was clear that reading a map like felt a lot of work. Time to make our life easier.

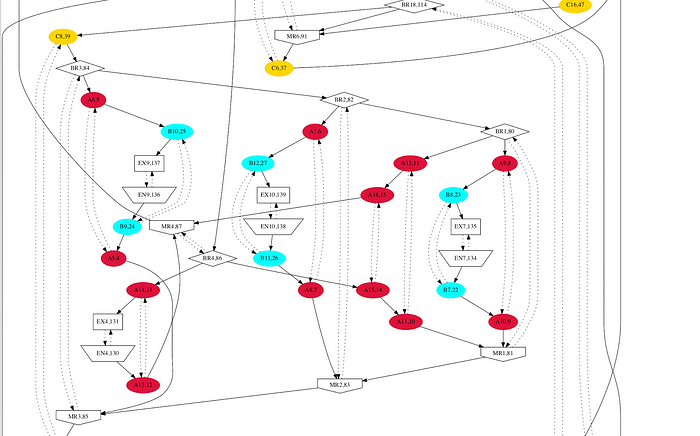

This tree map didn’t take much more effort, it was generated by GraphViz in the Dot language.

Tools empower you to be more productive. As a programmer, you’re always thinking about how to make things automated, and easier. A commonly seen trait that programmers have is to be lazy, a desire to automate things and make their own lives easier. Determine how much time you spent doing some work, and see if you can build a tool to make it easier.

Invest in building better tools when you find yourself repeating a task, as a rule of thumb, more than three times.

It’s ok to take on technical debt. Keep it simple, stupid.™

For example, having fancy colorful terminals. Ours was initially very pretty, but we noticed a lot of things had to be changed. Towards the end of the projects, we had avoided building fancy graphics because they took a lot of work and are likely to be changed later.

If you wanted to have pretty looking terminals, lot of time had to be dedicated for it. If you’re really bored, and have time to kill, I suppose it’s fine.

Later on, we took on more technical debts with screen drawing. It no longer looked as nice, but it worked.

If there are technical debts with higher priority, they should be addressed before diving into a lesser problem.

This sounds intuitive, but sometimes people become irrational and just spend time on low priority issues. Like making things look pretty.

Pair programming is effective teamworking.

Initially we dividing up projects, and mostly worked separately. This was okay for well-defined problems, as it was the case for initial kernel implementation. But later on, the problems we needed to solve became so inter-dependent that it was no longer feasible to build something in the dark.

Many quick idea iterations were needed, and we needed each other to bounce ideas around. Having a comfy couch is important!

And towards the end, we were doing pair programming out of despair; we had to write working code, and we had to write it fast.

Pair programming produces quality code that is better thought out, and a rate that is comparable, if not faster, to separating out tasks and doing code reviews.

Summary

I think taking this class was very valuable, and was a very nice way to wrap up my Computer Science undergrad.

These lessons are ingrained in my memories, and helped shape my behavior.

For example, after pair programming, I subconsciously debate about solutions to problems and bounce ideas around. To an outsider, it may seem argumentative, but it’s really an effective way to solve problems.

Thank you for reading.